Rain gardens are growing in popularity as an attractive, cost-effective way to manage stormwater – they help prevent flooding, naturally filter out pollutants to protect water quality, and reduce stress on municipal water management infrastructure.

At the same time, there are many misconceptions – even amongst landscape professionals – about what a “rain garden” actually is.

Here are some things rain gardens are not:

- They’re not ponds.

- They don’t need to hold water long-term or require pond-loving plants.

- They’re not wetlands or boggy areas that flood a lot.

- They’re not swales (depressions or ditches that direct runoff within a landscape).

- They’re not breeding grounds for mosquitos (because they’re designed to allow rainwater to completely drain into the ground within a 24-hour period).

For an expert definition of what a rain garden is, we talked to Jeff Thompson, an environmental biologist at Thompson Environmental Planning & Design Ltd. in Kitchener, Ont., who has been designing and building rain gardens for 20 years.

Thompson teaches landscape design professionals and contractors how to design and properly build rain gardens, and he’s helping establish a standard definition for a rain garden for Landscape Ontario, which represents more than 2,000 horticulture professionals in the province.

According to Thompson, a rain garden is “the most cost-effective way” of capturing rainwater that runs off hard surfaces like roofs, driveways and parking lots. Rain spouts direct the water into the garden, which soaks it up like a sponge and allows it to infiltrate the ground where it is naturally cleansed of contaminants as it returns to the aquifer. Reducing the amount of stormwater flooding into street gutters and down storm drains alleviates problems with underground infrastructure and keeps contaminants from polluting rivers and lakes.

In addition, rain gardens create excellent wildlife habitat and can be a beautiful addition to any landscape.

While “your imagination is the limit when it comes to designing a rain garden,” Thompson says they should include five critical components:

- a formal inflow and outflow (the outflow discharges to a safe location any water the rain garden can’t handle)

- “armouring” of the inflow and outflow with rocks and stones to prevent erosion

- a maximum amount of void “pore space” or air pockets in the planting mix to hold the rainwater, achieved by mixing 1/3 topsoil, 1/3 coarse sand and 1/3 mulch (ideally compost or shredded hardwood bark – pine mulch tends to be too acidic)

- only native plant species for optimal infiltration (due to their deep root systems)

- a monitoring device (this can be as simple as a one-inch pipe that reaches the bottom of the rain garden with a stick in it that you can pull up to see how much water is in the garden bed).

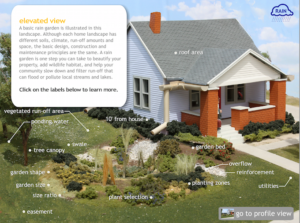

To see how a rain garden works, check out this fabulous animated infographic from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of Agronomy and Horticulture. (Click the rain cloud in the top right corner of each view!) (Thanks to Vivienne Blyth-Moore of Fern Ridge Landscaping for sharing this via her @vblythmoore Twitter feed!)

A rain garden in action, from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of Agronomy and Horticulture

Rain gardens can be located in either a front yard or backyard, and in sunny or shady conditions (which will affect your choice of plants). Thompson recommends choosing a location based on the following guidelines:

- 3 metres away from a building foundation

- 4 metres away from a septic bed

- 30 metres away from a well to avoid any contamination

- outside tree driplines

- locate and avoid underground utilities

- avoid steep slopes

- avoid the lowest point on your property (where water already collects) – you want to corral that water before it gets there to avoid ponding

If you have a property with special challenges – such as one plagued by runoff from neighbouring properties – consult a professional who may recommend a combination of actions to solve the problem.

Ideally you’ll want to build a rain garden of a size equal to 10-30 per cent of the area (e.g., your roof) that the water is being collected from. Beyond that your imagination is the limit: they can be any shape (crescent, kidney and teardrops work well) and formal or informal in design.

“When rain gardens are done and done properly, they look like a regular garden and they have all the benefits of a regular garden,” Thompson says. “They look great, they attract pollinators.”

Do you have questions about rain gardens or pictures of one you have built? We’d love to hear from you – send us a note via our comment box below. And stay tuned for more on rain gardens from Milkweed Journal – subscribing (see the form in the lower right corner) means you won’t miss a post!

© 2016, Milkweed Journal. All rights reserved. This article is the property of Milkweed Journal. If you would like to use a short excerpt, please provide credit to Milkweed Journal and include a link back to the original post on our site or use the social sharing tools available along the side. Please use our contact form below if you have any questions. Thank you!