In 1864, the American naturalist John Muir was on a mission, trekking deep into Ontario’s Holland Marsh, in search of a rare orchid.

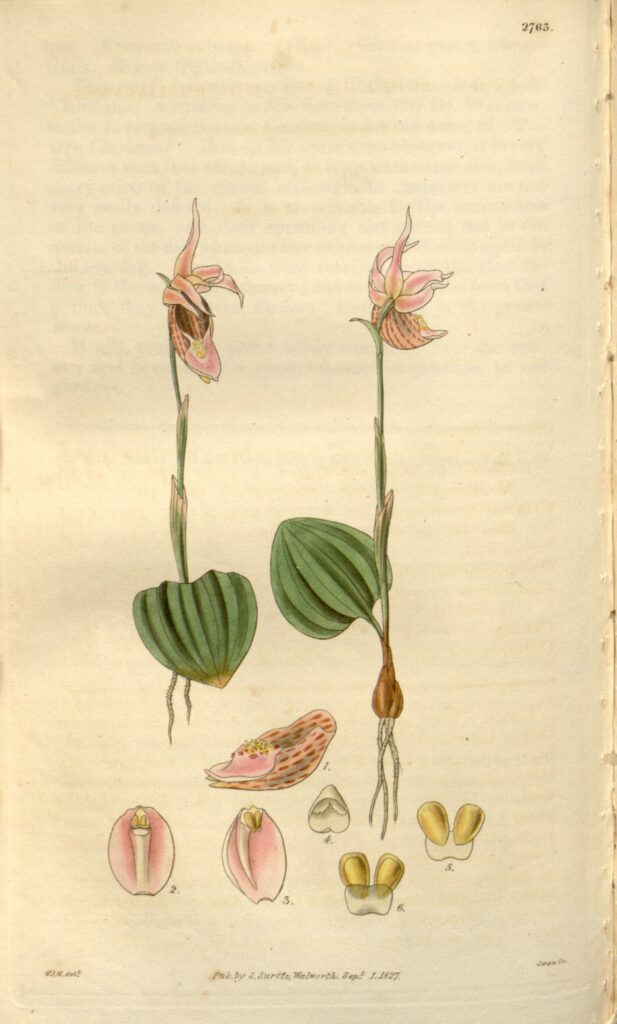

The object of his quest: the tiny, magical Calypso (Calypso bulbosa), or Fairy Slipper.

Muir was in his mid-20s, enthralled by botany and yet to publish his first writing.

His travels exploring Ontario’s flora took him along the Niagara Escarpment and much of what would become the Bruce Trail 100 years later.

Calypso is one of our smallest native orchids, and often called the most beautiful.

In Muir’s time it went by the arguably more charming botanical name Calypso borealis.

The Hider of the North

Calypso is among the first plants to bloom in spring in moist woodlands. But even in bloom, its single dainty pink, magenta or white flower on a slender stem is incredibly difficult to spot, earning it the epithet The Hider of the North.

The story of Muir’s quest for Calypso became the subject of his first published writing, sent in a letter to a friend and on to a newspaper.

Below is an account that Muir wrote years later, which was published after his death in 1924 in The Life and Letters of John Muir edited by William Frederic Badè:

“The rarest and most beautiful of the flowering plants I discovered on this first grand excursion was Calypso borealis (the Hider of the North). I had been fording streams more and more difficult to cross and wading bogs and swamps that seemed more and more extensive and more difficult to force one’s way through. Entering one of these great tamarac and arbor-vitae swamps one morning, holding a general though very crooked course by compass, struggling through tangled drooping branches and over and under broad heaps of fallen trees, I began to fear that I would not be able to reach dry ground before dark…

But when the sun was getting low and everything seemed most bewildering and discouraging, I found beautiful Calypso on the mossy bank of a stream, growing not in the ground but on a bed of yellow mosses in which its small white bulb had found a soft nest and from which its one leaf and one flower sprung. The flower was white and made the impression of the utmost simple purity like a snowflower. No other bloom was near it, for the bog a short distance below the surface was still frozen, and the water was ice cold. It seemed the most spiritual of all the flower people I had ever met. I sat down beside it and fairly cried for joy.

It seems wonderful that so frail and lovely a plant has such power over human hearts. This Calypso meeting happened some forty-five years ago, and it was more memorable and impressive than any of my meetings with human beings excepting, perhaps, Emerson and one or two others.”

Today, Calypso is found across Canada and the U.S., although it is listed as threatened or endangered in several U.S. states. And it is presumed extinct in the Holland Marsh, now largely given over to farming.

The Trout Hollow property where Muir worked and lived near Meaford, Ontario has been donated to the Escarpment Biosphere Conservancy.

And each year, the Calypso Orchid Environmental Award recognizes those who contribute to restoration and preservation of the Bruce Trail or the Niagara Escarpment Biosphere Reserve.

You can learn more about Calypso and other North American orchids from the North American Orchid Conservation Centre.

Thank you for reading. Enjoy your day,

— Stacey