This is the time of spring ephemerals, the first flowers to grace our gardens and natural areas as the weather warms.

Hepatica (Anemone hepatica), Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica) and bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), which I mentioned in last week’s post, are all examples of spring ephemerals native to Ontario and throughout Eastern North America.

The trillium is another much-loved ephemeral, as is the lovely trout lily (Erythronium americanum), the umbrella-like mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum), the utterly unique Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum) and the charming wood poppy (Stylophorum diphyllum).

Typically found in rich woodlands, and increasingly in native plant gardens, spring ephemerals awaken early to take full advantage of the sunshine before the tree canopy fully leafs out, returning to dormancy in the summer months.

More than a beautiful sign of spring, ephemeral wildflowers play an important role in the biodiversity of forest and wetland ecosystems, supporting bees and other early pollinators.

Unfortunately the survival of many of these native plants in the wild is threatened by habitat loss, the relentless spread of invasive species, and climate change.

Signs of change – in the 1800s

Botanist and author Catharine Parr Traill, who spent much of her lifetime studying Ontario wildflowers, witnessed the effects of habitat destruction on native plants in the 1800s.

She lamented this loss in her book Canadian Wild Flowers, published in 1868.

Catharine wrote of her desire “to foster a love for the native plants of Canada, and turn … attention to the floral beauty that is destined sooner or later to be swept away, as the onward march of civilization clears away the primeval forest—reclaims the swamps and bogs, and turns the waste places into a fruitful field.”

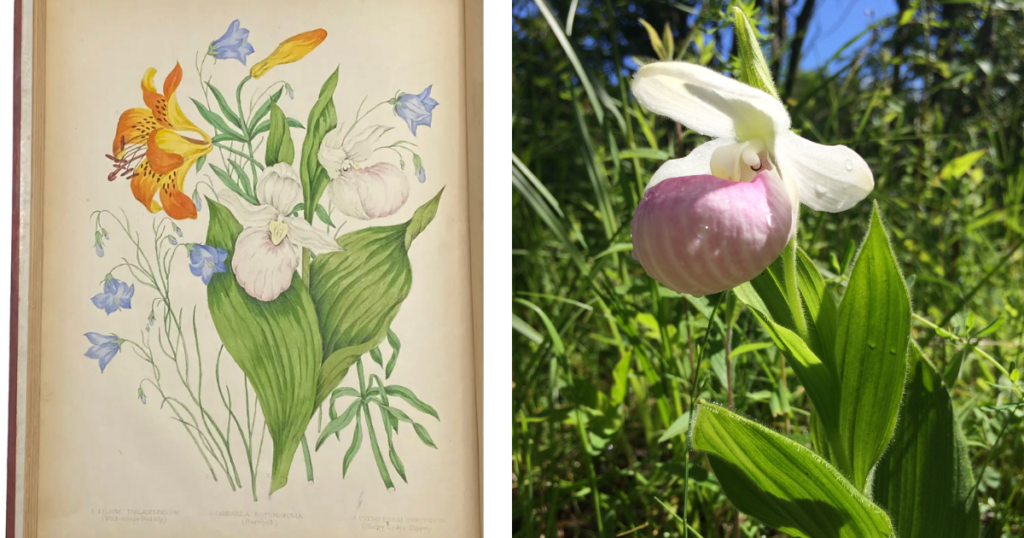

In the book she described several spring ephemerals, with illustrations by her niece Agnes Dunbar FitzGibbon.

A rare orchid ephemeral: Showy Lady’s Slipper

Among them is Showy Lady’s Slipper (Cypripedium reginae / Cypripedium spectabile), a rare member of the orchid family that has now disappeared from much of its historical range.

“Whether we regard these charming flowers for the singularity of their form, the exquisite texture of their tissues, or the delicate blending of their colours, we must acknowledge them to be altogether lovely and worthy of our admiration,” Catharine wrote.

Hidden treasure

Two Showy Lady’s Slipper plants grow at my parents’ former property in an almost hidden spot beside a spring-fed pond. This orchid can take more than 16 years to bloom and a single plant can live more than 50 years.

We felt so lucky to see them year after year, hoping and trusting that they would continue to return to that protected spot.

Here fleetingly, and then invisible once again – the spring ephemeral life cycle is a metaphor for our own life journey, and a symbol of awakening and renewal.

It reminds us to enjoy the beauty of each and every day, and each and every season.

Thank you for reading. Enjoy your day,

— Stacey

P.S. See this Ontario Nature blog on why wetlands are so important and how to add your voice to saving them.